It’s time to explore the how video games can expand and enhance the reader experience by building upon what an author created in book form {parts I & II of this miniseries explore other aspects of the reader experience via video games}.

When I’m teaching bookbinding I tell students that the history of books is tied to the history of storytelling and the history of storytelling {by humans} begins whenever you decide to start counting. First, stories were told orally, two great examples that made it to print form are Beowulf and the stories collected by the Brothers Grimm (Headley, 2020). Oral storytelling continues today, imagine it running alongside other forms of information sharing. There were also cave paintings and drawings, the downside being that if you wanted to learn about your dad’s childhood you had to go all the way to the cave where he painted the tale to learn more. Stories became portable with stone, clay, and wax tablets and also scrolls. Sometime in the 4th century CE in Egyptian Coptic Christians created the earliest known codex- a book with the pages held together all on one side; opening not the otherside. This is the book format we are most familiar with today (Houston, 2016). Sixteen centuries later some dudes on the West Coast of the United States brought computing down to a personal scale and information and stories could be shared digitally; which brings us to the present day.

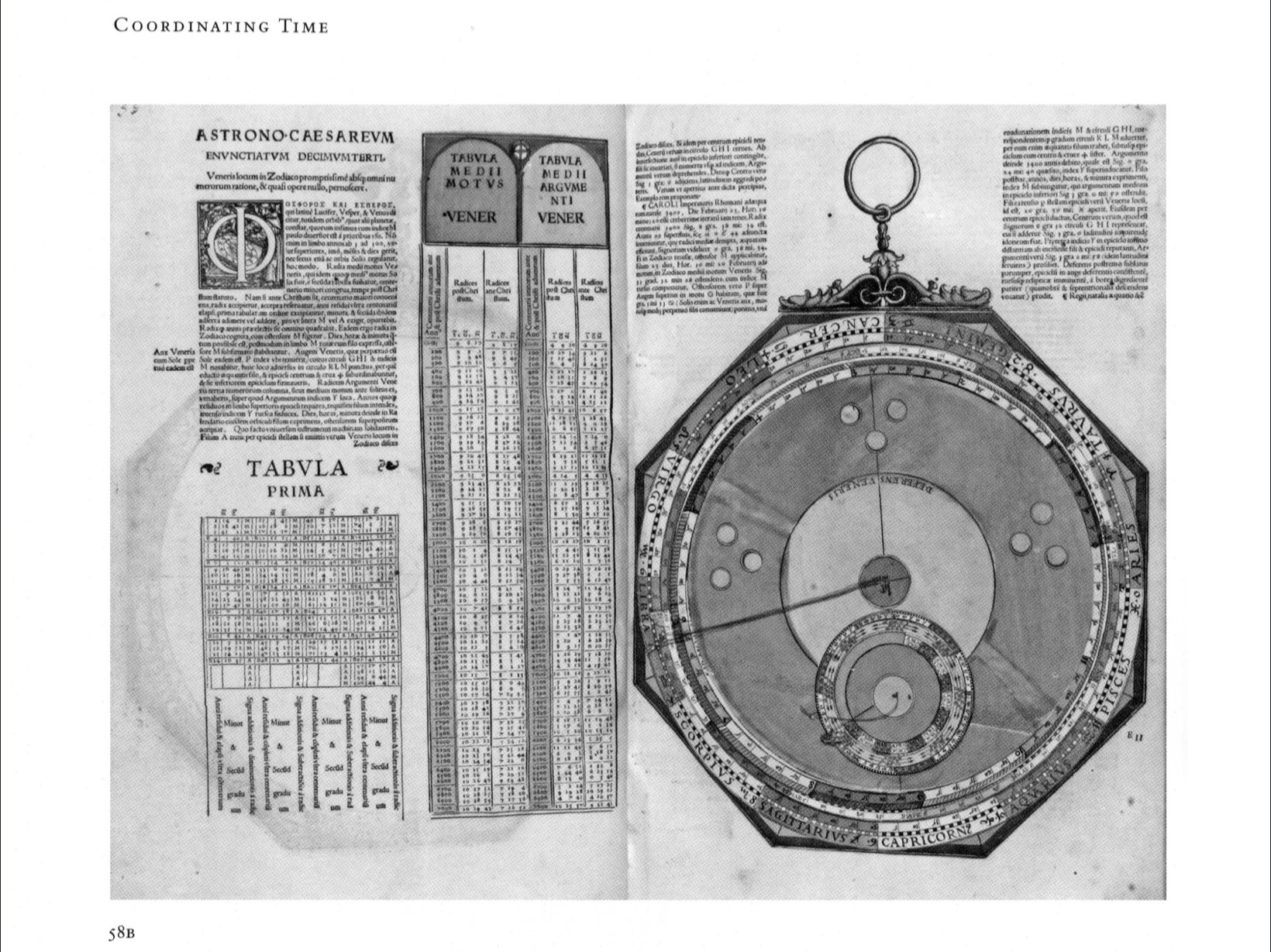

Some digital formats and stories simply recreate the print versions and that’s just fine. Others, like video games, allow for an expansion of the world and story in ways the authors might never have dreamed of. While the games we’ll look at below take textual enhancements to an extreme, books with added elements to engage the reader/user are not at all new. In 2005 the University of Chicago hosted an exhibition titled Book Use, Book Theory: 1500-1700 which looked at elements contained in books that created a reader experience that went beyond reading. While I didn’t see the exhibition in person, the catalog is available online and my favorite part was Part IV: Dimensional Thinking. The books in this section contain pop-ups and volvelles which ask the viewer to engage with the physical space inside a book. The curators of the exhibit ask viewers to think about engagement beyond the act of reading (University of Chicago Library). They suggest that “thinking through books means thinking in and around them” (Cormack and Mazzio, 2005, p. 6). Taking a broad view of “thinking in and around” books we come to the book-based worlds created in video games.

Image of layered volvelles in a book from the University of Chicago exhibit Book Use, Book Theory (Cormack and Mazzio, 2005, p. 100).

There are many games that are set in book-based worlds, I’m going to briefly look at three to whet your appetite.

There are a lot of Middle-Earth based games with no end to the relationships you can build with the humans, wizards, orcs, hobbits, elves, and dwarves from J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy. Because Tolkien created not just captivating stories but also lineages for his characters, languages, extensive maps, and folklore, he left the doors wide open for others to build within and around Middle-Earth. Beloved and hated characters, creatures, and story lines are reintroduced in Middle-Earth: Shadow of War where players must both fight and befriend orcs using a newly forged ring of power as they try to get to Mordor amidst Sauron’s growing power. Players can even befriend Shelob! The game stays firmly rooted in Tolkien’s world while adding more nuance, the enemies of the Fellowship are not necessarily without their uses here (Kelly, 2017). The game connects to the story enough to entice those that enjoyed reading the original stories to explore new corners of Middle-Earth and encourages newcomers to look into the source material.

Image of three The Witcher book covers

Thanks to the Netflix series of the same name, The Witcher saga is well known in 2021. The tales began as a series of short stories that grew to include five novels, originally published in Polish then translated into English and released in the US beginning in 2007 (Hatchett Book Group, n.d.; Wikipedia). The trilogy of games takes their connection to the books seriously (note the covers in the image above have characters from the game). CD Projekt Red, the games’ creator, states that “being based on a novel series…gives the game’s universe and characters credibility” (thewitcher.com). Both the novels and the games follow the story of the Witcher Geralt; in the games players move through the world as Geralt and instead of following the pre-determined path set by the books, the player must make their own decisions and wait to see what the consequences are. Non-playable characters (NPCs) can also be influenced by Geralt’s actions, creating a world where side characters are important to the story, not unlike a book. The Witcher games extend the world created by author Adrzej Sapkowski while staying true to characters and creatures, once again opening reader engagement opportunities not possible in the print versions of the tales.

Ok, I can’t talk too much about this game and book relationship yet because the game, Hogwarts Legacy, isn’t released but I think it’s important to mention because the Wizard World has done a lot to expand the world J.K. Rowling created in the seven book series. Readers like myself, who are still waiting for their Hogwarts letters to arrive, will get their chance to be a Hogwarts student in this game. Set in the 1800s, readers and players will put special magical abilities to use as they make friends and battle dark wizards (hogwartslegacy.com). The tagline for the game is “live the unwritten” (hogwartslegacy.com) drawing a direct connection between the games and books and encouraging those who haven’t read the series to check them out.

Volvelles, pop-ups, maps, and charts have expanded the reader experience on the page for centuries, the invention of digital technology and the creation of video games based on books allow readers to take their reading experience off the page into an immersive experience.

Citations

CD Projekt Red. (n.d.). The Witcher: Enhanced Edition. The Witcher.Com. https://thewitcher.com/en/witcher1

Cormack, B. and Mazzio, C. (2205). Book use, book theory: 1500-1700. University of Chicago Library

Hatchett Book Group. (2021, June 24). Andrzej Sapkowski’s Witcher Books in Order. Hachette Book Group. https://www.hachettebookgroup.com/series-list/andrzej-sapkowski-witcher-books-in-order/

Headley, M. D. (2020). Beowulf: A new translation. MCD x FSG Originals.

Houston, K. (2016). The book: A cover-to-cover exploration of the most powerful object of our time. W. W. Norton & Company.

Kelly, A. (2017, October 5). Middle-earth: Shadow of War review. Pcgamer. https://www.pcgamer.com/middle-earth-shadow-of-war-review/

Portkey Games. (n.d.). Portkey Games: Hogwarts legacy. Portkey Games: Hogwarts Legacy. https://www.hogwartslegacy.com/en-us

The University of Chicago Library. (n.d.). Book Use Book Theory - Book Use, Book Theory. https://www.lib.uchicago.edu/collex/exhibits/book-use-book-theory-1500-1700/