“…and romance is a reflection of the acceptance in society as well…People like themselves being heroes, hunting zombies, getting happy endings” (Jones, 2015, p. 24 & 26).

Introduction

Romance is one of the most popular genres of literature. Like all types of literature, it is constantly evolving, and its readers are constantly seeking new fictional experiences. One of the changes within this genre is the inclusion and centering of a diverse range of characters, including those that identify as BIPOC, LGBTQIA+ (queer), and neurodiverse. This diversification is apparent when looking at Romance novels on a library or bookstore shelf however there is little discussion of this diversification or its importance in academic literature. A textbook resource published in 2019 by the American Library Association, for librarians and those studying to become library professionals, centers a heteronormative and monogamous definition of the genre offering examples that primarily feature white characters. This is problematic because it marginalizes the existence of diverse stories and marginalizes the experiences of diverse scholars and professionals along with Romance readers. It could also make it challenging for proper representation to occur at the institutional (library) level. Discussions of the diversifying genre do exist in popular magazines and media and there are new definitions being used. This paper attempts to give an overview of the issue at hand, the discussions of diversity taking place, alternative genre definitions, and their importance. It concludes with a plea for more research into the importance of the diversity that currently exists within the Romance genre.

The problem at hand

The Readers’ Advisory Guide to Genre Fiction, Third Edition by Neal Wyatt and Joyce G. Saricks (2019), defines Romance books as novels that

“focus on the emotional and physical union of two central characters. Romances stress the conflicts and resolutions within this union and are centrally concerned with the emotional satisfactions of the resulting relationship. Romances are novels of courtship, love, mutual respect, and appreciation” (Wyatt and Saricks, 2019, p. 216).

The definition goes on to stress that the “focus on the developing relationship between two characters and the reader’s vicarious emotional participation in that union are central to Romance fiction” (Wyatt and Saricks, 2019, p. 216). In describing the characteristics of Romance, the authors use only binary gender terms and binary gender stereotypes. “Men are powerful, confident, and slightly dangerous; women are strong, bright, and independent” (Wyatt and Saricks, 2019, p. 216). Throughout the rest of the chapter the protagonists are described using terms like “hero” and “heroine” thus reinforcing binary gender stereotypes. There is a nod to diversity, but it doesn’t come until the second to last page with a discussion of “mixed-race” and “same-sex couples” boiled down to one sentence. There is no mention of neurodiversity, or the array of possibilities being explored in along the gender and sexuality spectrums (Wyatt and Saricks, 2019).

While parts of this definition could apply to a wide variety of characters and love stories, the language chosen throughout the 18-page chapter reinforces an outdated understanding of romance in general and does little to represent where the Romance genre is today. The closest definition to the one used by Wyatt and Saricks that research for this paper turned up is from a 1999 article that quotes the Romance Writers of America (RWA). At that time the organization defined romance novels as

“stories whose main focus is the relationship between a man and a woman. The most important aspect of a romance novel, and what identifies it as such, is the guaranteed happy ending, the establishment of a commitment between one man and one woman” (Black Issues Book Review, 1999).

It is important to note that the RWA has since updated their definition; this will be discussed later in the paper. Thus, while the textbook definition of Romance is historically true, it is possibly 20 years out of date.

Attempts to find academic research that would support a new definition or support the importance of diversity within the Romance genre was frustrating at best. It appears that not much research in this area has been done. Articles that came close in search results for “queer romance” are ostracizing. Results included titles such as Freaks of Fancy: Queer Temporality and Pleasures of Power Play in Female Quixotism, Blessing Same-Sex Unions: The Perils of Queer Romance and The Confusions of Christian Marriage, and How to Make a Heterosexual Romance Queer… These titles are not the only ones in the search results, but they do appear at the top of the first page of limited results. While reading these articles and discussing the problematic titles is beyond the scope of this paper, they do further emphasize the issues with language that exist at an academic level and can lead to feelings of alienation in scholars and researchers that identify as LGBTQIA+. It is possible that research in queer Romance novels exists but, it does not turn up in results for “queer romance,” “LGBTQ romance,” “gay romance,” or “lesbian romance.” Which leads to the question that if this research exists but cannot be found based on the terminology used within the community it pertains to, what vocabulary is being used? How are professionals seeking to further their field and assist an increasingly diverse range of patrons supposed to support and validate this work if it is so difficult to find?

Screenshots of search results in Academic Search Complete

In the one article that was found in a trade journal, a more general definition of Romance is used however, diverse titles are separated from the discussion of changes to the more heteronormative books in the genre. The article uses sub headers for subgenres such as Romantic Comedy Reigns, Comforting Reads, Strong Women, …And Sexy Men, Love Through the Ages, Beastly Tales, and Kept in Suspense, The article does not mix multicultural, queer, or neurodiverse titles into these subgenres even though these diverse novels could easily land in these categories. Instead, subtitles like Multicultural Crossover, New in LGBTQ+, and What’s Next: Neurodiversity, are used, further singling out diversity instead of welcoming it into the genre at large (Howe, 2015). While this article was written in 2015 and more recent articles about the diversity in Romance in Library Journal were not discovered in a database search, which could indicate an integration over the subsequent years, this separation has a lasting impact given that the 2019 edition of The Readers’ Advisory Guide to Genre Fiction continued the trend of separating out diverse examples of the Romance genre.

“But a void is just an opportunity” (Palfrey, 2005, p. 17).

Photo taken by the author; location discussed in Acknowledgements

Counter evidence to the textbook definition

Wyatt, Saricks, and the ALA cannot hide behind the fact that their textbook was published three years ago (at the time of this writing). In 2015, Publishers’ Weekly was reporting on the fact that Romance “titles encompass the full range of subgenres: historical, contemporary, science fiction, fantasy, paranormal, and mystery. “We have stories that [include] every type of romance trope”” (Jones, 2015, p. 26). Also, if the recent onslaught of book bannings in public and school libraries, which primarily target books about BIPOC and LGBTQIA+ experiences, are any indication, diverse titles are being added to library shelves by professionals in the field. If updated language surrounding Romance novels is not being discussed in academia and other professional literature, where are these conversations happening? Are they important? These issues are being talked about at the ground level, in organizations that exist outside academia, in popular magazines, and book review sources. Diverse titles are being included on library and bookstore shelves. As authors are quick to point out and news sources rush to report, diverse representation in literature is important. Below is a survey of the conversations that are taking place.

It is not as if queer romance stories are new. According to a Slate article, lesbian romances came onto the literary scene in the 1970s and were closely followed by gay romances a few years later, though they may not have been deemed Romance at that time (Grimaldi, 2015). While it took some time to catch up, the Romance Writers of America now define the genre as having “two basic elements: a central love story and an emotionally satisfying and optimistic ending” (RWA, n.d., Definition). It is also important to note that under a header titled The Basics, the RWA states “Romance is smart, fresh, and diverse” they go on to emphasize that regardless of what readers enjoy, “there’s a romance novel waiting for you!” (RWA, n.d., The Basics). It is unclear exactly when this change took place but there was a recognition of the evolution the genre was undergoing, and the vocabulary was adapted to meet these advances. This new verbiage makes evident a disconnect between how the authors of the genre describe their work, how readers understand the genre, and how those being trained in the book industry learn to understand the genre.

The diversity within the genre is also actively being discussed in popular news sources by the authors themselves. In a 2021 TIME Magazine article titled How to write a romance novel in 2021, author Annabel Gutterman tackled the historical understanding of the genre as one that “has centered stories by, for and about a homogenous set of women, bolstering the stereotype of straight white women as the romantic ideal…” (Gutterman, 2021, p. 100.). In the piece Gutterman interviews six Romance authors actively diversifying the genre. Married writing duo Mikaella Clements and Onjuli Datta echo the updated RWA definition stating “there are many things about love which are universal” (Gutterman, 2021, p. 101). When asked why it is important for these authors to share their diverse lived experience via Romances, the authors talk about the importance of representation for readers with similar experiences as well as how these books can create a sense of empathy among readers who have not had these experiences. Diverse Romance books also offer an opportunity for social commentary within well-known tropes. These books can become a safe place for authors and their readers to question societal norms which could lead to greater understanding and empathy in the real world (Gutterman, 2021).

“Lots of people think romance is cheap, trivial, and the literary equivalent of pornography. To me, it’s an escape, catharsis, a bridge to build empathy, even a political or social statement, all while providing a full mind, heart, and body experience” (Gutterman, 2021, p. 100, quoting neurodiverse Romance author Helen Hoang).

Preliminary research conducted in 2015 in the field of psychology offers some evidence to support the fact that readers of fiction do develop a greater sense of empathy for those in situations unlike their own. Fong, Mullin, and Mar used four fiction genres, including Romance, to study the effects reading fiction has on generating greater understandings of lived experiences and societal situations among over 300 research participants. Their evidence suggests that “fiction exposure predicted greater egalitarian gender roles, less endorsement of gender role stereotypes, and lower levels of sexual conservatism” (Fong, Mullin, and Mar, 2015, p. 277). This aligns with earlier research cited in the same study that found similar results. One of these studies found that participants who read a story about a gay man experiencing homophobia were more likely to understand homophobia from the perspective of those who experience it (Fong, Mullin, and Mar, 2015). Unfortunately, not much academic research has investigated the effects of the rapidly diversifying Romance sphere, but anecdotal lived experiences also contribute to this evidence.

Black Romance author Evelyn Palfrey discusses the challenges of having to imagine blond heroines as having hair like hers as a Romance reader growing up (Palfrey, 2005). She also discusses the importance of ethnically diverse Romances challenging societal prejudices.

“What I love about romance novels is that is the one place where our good men can get some play. Certainly not in the mainstream media. Lawd, if the Martians landed here and only read the newspapers and watched television, they would get the impression that all of our men are dangerous—that they are all drug dealers and they all carry guns…But our husbands, boyfriends, sons, uncles, and grandfathers aren’t all like that” (Palfrey, 2005, p. 17).

Though fictional, these books offer a window into a reality that many readers aren’t shown when reading nonfiction sources. Writing novels with more diverse representation not only benefits the authors. While queer author Casey McQuiston admits to writing the Romance novels she wanted as a teenager, her first book, Red, White, and Royal Blue, “found an eager audience” and quickly ended up on the New York Times bestseller list (Gutterman, 2021, p. 104).

Photo taken by the author; location discussed in Acknowledgements

The importance of representation was described above but what is the harm that a lack of representation leads to? Looking into news reports about recent book bans can help to understand this question. In some states, such as Texas, politicians are attempting to pass legislation that would allow for the prosecution of anyone providing a profane book to someone under the age of 18. The Progress Texas article citing this information begins by pointing out that “books are integral to free expression” and yet this legislation undermines the validity of BIPOC and queer youth and criminalizes their friends, family, and allies (Cadena, 2022, 1st-4th paragraphs). NBC news is reporting similar issues regarding the banning of LGBTQIA+ books taking place in Florida. There is also a “don’t say gay” movement taking place there which would prohibit any discussion of sexuality and gender identity (Lavietes, 2022). While this may seem to stray from the point of the need for academic discussion of diverse Romance novels, it does not. If diverse authors are writing to fill a void and readers are embracing these novels, then there is a need for them, and they are valid. Saying these books are valid means that these experiences and people who live them are valid. Seeing these books mixed in with all the other authors on library shelves helps to normalize the diverse range of human experiences and identities, while removing and banning these books erases these communities. Evidence is needed to support or invalidate any claims made and where does that evidence come from? Often it comes from academic research. Holes in academic research and outdated vocabulary used to train professionals is a dangerously slippery slope and could hinder the preservation of intellectual freedom.

hoto taken by the author; location addressed in Acknowledgements

“Don’t join the book burners. Don’t think you are going to conceal thoughts by concealing evidence that they ever existed.” (Dwight D. Eisenhower; from a poster the author owns).

Conclusion

One article that was discovered in a trade journal, Library Journal, stated in 2015 that “when it comes to romance, the best stories provide swoon-worthy escapism with real-life problems” (Howe, 2015, p. 27). Clearly, based on the evidence cited above, the defining characteristic of a Romance novel is not who is in love or how they identify, but rather the fact that everyone in depicted in Romance deserves and gets a happily ever after. Yet the question remains as to why this definition is not reflected in the academic literature.

This essay is not the one that was intended to be written. The original essay was supposed to be easy. It was going to look at an outdated definition of the Romance genre and update it based on academic findings. With all the gender, sexuality, and diversity studies programs at colleges and universities, this was bound to be a topic that was over-researched. The main argument was just going to be that a new textbook was needed that is more aligned with the times. Unfortunately, the research that was expected in large part didn’t exist. Especially not in academic and trade journals. Using sources pulled from popular media can be dangerous in academia but, for better or worse, these are the spaces where the discussion about diversity in Romance novels is happening. The discussions in peer-reviewed and trade journals are sparse at best. This silence is the real problem that needs to be addressed. Students in library schools are taught at length about diversity, the need for creating inclusive and safe spaces, and to rectify past prejudices and segregation the institution participated in. However, at least in this instance, this is not reflected in the training materials. Librarians are smart people, as the book banning reports indicate, those on the job are keeping up with the times and following a variety of bookish news sources to learn about and incorporate new and diverse books that satisfy changing reader tastes and desires. Despite this, on the academic side there is a lack of scholarly research and writing about the importance of the increasing diversity in Romance fiction and its impact on readers.

Why has the American Library Association not redefined the genre in their own publication? It is far beyond the scope of this paper and this author to answer the question but, hopefully, the need has been made clear. The lack of diversity in academic literature can have a trickle-down effect. Seeing oneself reflected in literature can offer validation of lived experiences. Being reflected in non-discriminatory ways in academia can lead to wider variety of scholars who then become professionals in the field and thus diversify the field. Who wants to study something that treats them as an afterthought at the end of a chapter about one of the most popular fiction genres? Ultimately this author argues and begs academia to expand upon the work of popular media sources like TIME Magazine and Publishers’ Weekly and to discuss diverse Romance books and their impacts. Queer, BIPOC, and neurodiverse Romance has been in existence for years and is enjoyed by a range of readers. It encompasses all subgenres of Romance in ever-increasing varieties and should be mixed in with the reviews and research done of more traditional Romance literature. Welcoming it into the definitions and discussions will help to normalize diverse topics and people which can help to normalize these titles, people, and experiences in the real world which could then lead to greater acceptance in society.

“Romance readers want to see themselves reflected in the books they read, this should be a fundamental change to the makeup of the publishing landscape rather than a passing ‘trend’” (Howe, 2015, p. 28).

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to the staff at Bookshop West Portal who allowed the author to photograph the newly expanded Romance section. The staff was also willing to chat about the need for redefining the Romance genre due to the influx of diverse titles.

Citations

Cadena, A. (2022, February 24). You’re not welcome here: How book bans alienate Texas students. Progress Texas. https://progresstexas.org/blog/youre-not-welcome-here-how-book-bans-alienate-texas-students

Fong, K., Mullin, J. B., & Mar, R. A. (2015). How Exposure to Literary Genres Relates to Attitudes Toward Gender Roles and Sexual Behavior. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity & the Arts, 9(3), 274–285. https://doi-org.proxy.ulib.uits.iu.edu/10.1037/a0038864

Grimaldi, C. (2015, October 8). Reader, he married him: LGBTQ romance’s search for happily-ever-after. Slate Magazine. https://slate.com/human-interest/2015/10/lgbtq-romance-how-the-genre-is-expanding-happily-ever-afters-to-all-queer-people.html

Gutterman, A. (2021). Casey McQuiston masters the art of feel-good fiction. TIME Magazine, 197(21/22), 104–105.

Gutterman, A. (2021). How to Write a Romance Novel In 2021. TIME Magazine, 198(3/4), 99–101.

Howe, K. (2018). Love changes everything. Library Journal, 143(17), 27–31.

Jones, M. M. (2015). Finding Love In All the Right Places. Publishers Weekly, 262(23), 24–28.

Lavietes, M. (2022, February 21). From book bans to “Don’t Say Gay” bill, LGBTQ kids feel “erased” in the classroom. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/nbc-out/out-news/book-bans-dont-say-gay-bill-lgbtq-kids-feel-erased-classroom-rcna15819

Palfrey, E. (2005). Romance at any age: A daughter’s curiosity brings back a writer’s long-ago memories of sneaking Mama’s romance novels from under the bed and urges her to write for every generation. Black Issues Book Review, 7(1), 16–17.

Romance Writers of America. (n.d.). About the Romance Genre. https://www.rwa.org/Online/Romance_Genre/About_Romance_Genre.aspx

What is a romance novel. (1999). Black Issues Book Review, 1(4), 45.

Wyatt, N., & Saricks, J. G. (2019). The readers' advisory guide to genre fiction. ALA Editions.

Personal comments

This piece was turned in dangerously close to deadline. It was challenging not to write from a place of sadness or anger. It is clear that this topic needs more attention and study.

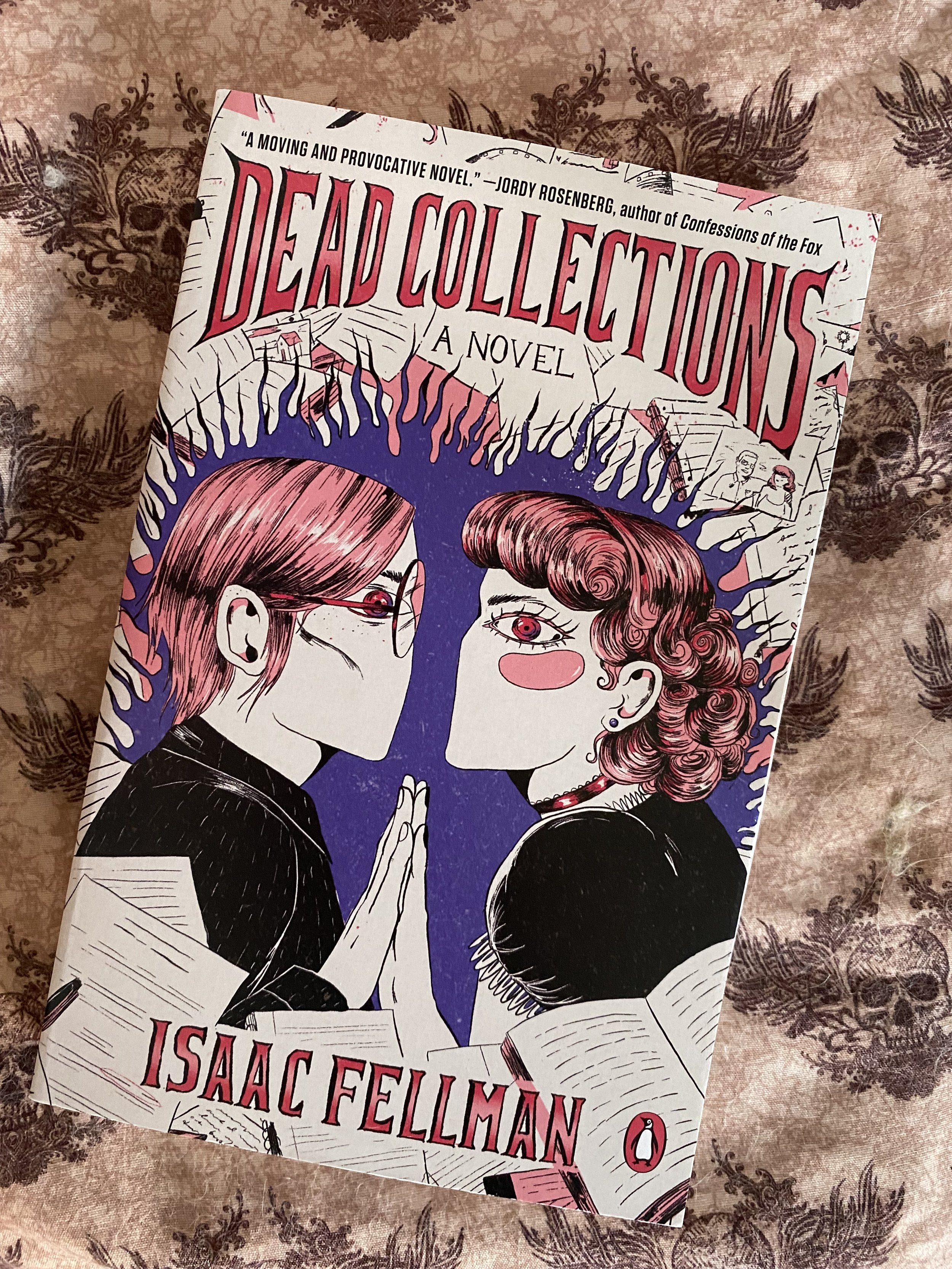

Photo taken by the author from their personal library.